As you open the dashboard to your onboarding flow, you see that conversions continue to trend downward as they have been for the last month. You review the numbers, see the potential impact on revenue, and see you won’t meet your goals for the year. A shot of adrenaline shoots through your body. A small sweat trickles down your brow…

Ok, too dramatic? Yeah, probably. But this is the reality for product teams every day. Teams will create war rooms over a few percentage points to see what they can do to revive a business.

As teams explore potential culprits for subpar numbers, the question is always—and rightly so—“How can we improve the business metric?” But what if we turned that question around and asked, “Where are we falling short in solving our users’ problems?”

When looking to improve business outcomes, we usually just focus on the needs of the business. However, business metrics aren't what make a business successful. It’s the users and customers that enable us to have metrics that are up and to the right.

The X → Y → Z Framework

To achieve a desired business outcome, we must understand how it impacts a user. Enter what I like to call the X → Y → Z framework to align user and business needs.

If we solve X user problem, it will lead to Y user behavior, resulting in Z business outcome. This framework can be worked backwards as well. If we want to achieve Z business outcome, we need to change Y behavior, and we can do that by solving X user problem.

The Framework in Practice

Let me walk you through a very real scenario. I’ll use a similar funnel example from the beginning of this post. Let’s imagine you work for a credit card company and see that your applications aren’t where you want them to be. The Z business outcome you want is a 5% increase in completed applications.

You look at the application funnel and see that out of every 100 people who enter the application process, 50 drop off on the information page. Another 20 drop off when asked for their employment and income information. Another 25 drop off when asked for their social security number. And another 3 drop off before clicking the submit button.

Let’s imagine that a couple months back your user researcher conducted a study and found that trust (or lack thereof) is a key component in users deciding to apply for a credit card with one company vs another. With that information in mind, let’s walk through a few scenarios I’m sure play out across teams in similar situations.

Scenario 1: Prioritizing Funnel Length

The team decided that removing the informational first page is the quickest way to address the drop-off. The rationale?

The page isn’t collecting user data—it’s just informational

The first page is just too clunky. No one reads all the text anyway

Shortening the flow will reduce perceived effort, thus increasing completions

Armed with this hypothesis, the team invested two weeks into reworking the funnel, removing the informational page, and running an A/B test. When the results come back, the numbers are disappointing: drop-off actually increased by 5%, leading to a net loss in completed applications.

Why Did This Fail?

By removing the informational page, the team unintentionally undermined a key user need: reassurance. Without understanding what to expect in the application process, users felt uneasy about proceeding. Questions about security, credit impact, and the type of information required went unanswered, eroding trust.

The assumption that shortening the funnel would increase completion rates overlooked the deeper role the informational page played in addressing user concerns.

Scenario 2: Prioritizing Trust

In this approach, the team revisited the original research to understand the nuanced role of trust in the user journey. They recognized that:

Users enter the funnel with questions and doubts

It is the job of the team to ensure users are comfortable every time they click the “Next” button

The informational page was acting as a trust builder but could be better optimized

Instead of removing the page entirely, the team worked to improve its clarity and usefulness:

Simplified the Content: Rewrote the copy to be concise and user-friendly, ensuring key points (e.g. “Your credit won’t be affected,” “Your information is secure”) were prominently displayed.

Trust Signals: Included prominent badges for security (e.g., “SSL Secured”), endorsements from trusted organizations, and a quick FAQ section addressing common concerns.

After implementing these changes, the team ran an A/B test. This time, the drop-off on the information page decreased from 50% to 30%, and overall funnel completion rates increased by 10%.

What Made the Difference?

Instead of seeing the information page as a bottleneck, the team viewed it as an opportunity to solve a user problem: the need for trust and reassurance. By addressing this problem while maintaining a focus on efficiency, they achieved both user and business goals.

Engagement-Driven Business Models

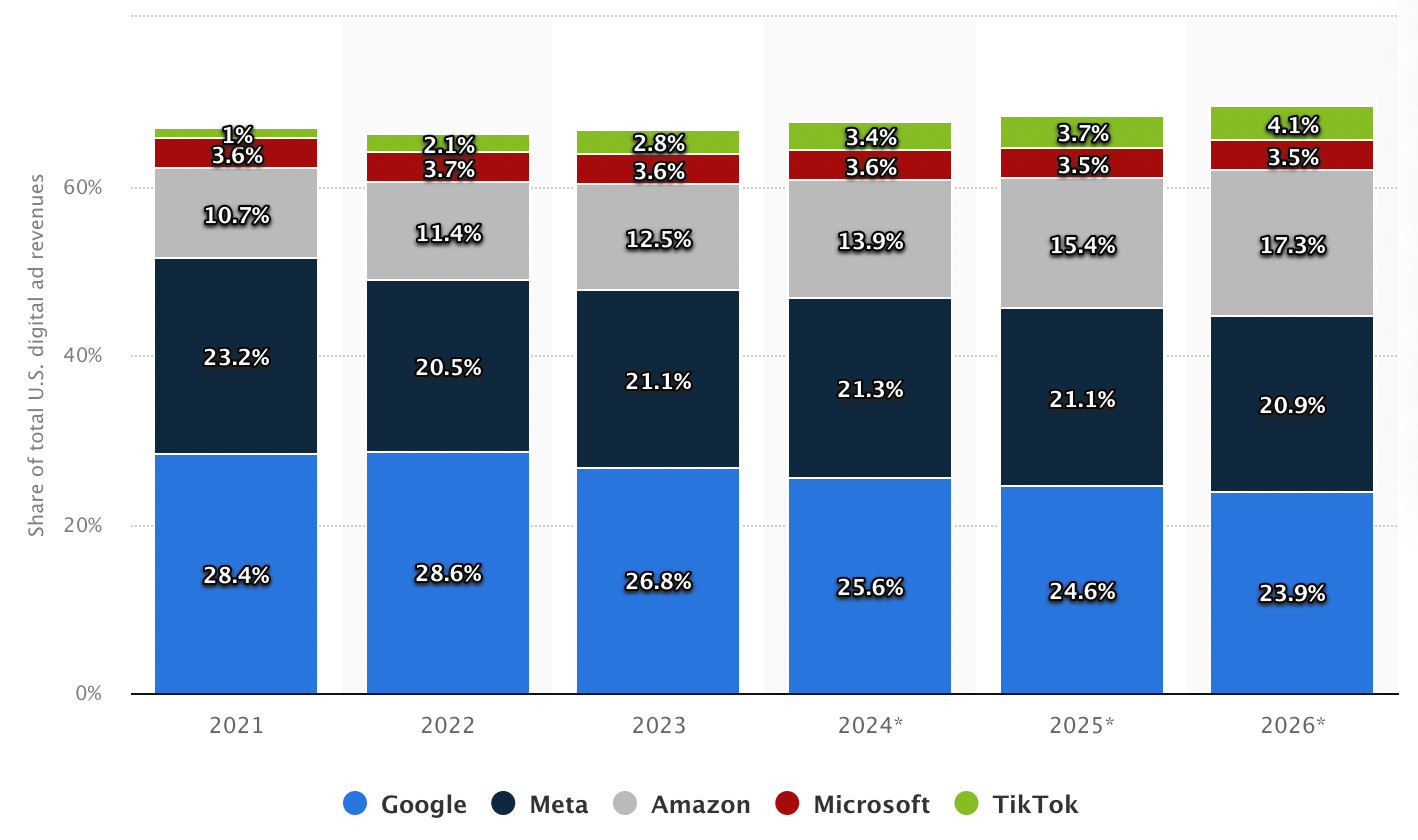

Let’s shift gears to an engagement-based business model, where the relationship between user needs and business outcomes isn’t always straightforward. Engagement-based business models are when companies generate more revenue the more a user engages with the app. Companies like Google, Meta, and Amazon generate significant revenue from ads, yet the user problems they solve often don’t align directly with the business need to show more ads.

For example, a product manager at a company such as TikTok might ask, “How can we increase ad impressions to boost revenue?” On the surface, this question centers entirely on the business problem. But let’s apply the X → Y → Z framework to explore the intersection of user and business needs:

X (User Problem): TikTok users come to the platform to be entertained and discover interesting content—not to see ads.

Y (User Behavior): If users encounter too many irrelevant or intrusive ads, their engagement drops—they scroll less, leave the app sooner, or even stop using the platform altogether.

Z (Business Outcome): Lower engagement leads to fewer ad impressions and reduced revenue, directly undermining the business goal.

The challenge for an engagement-driven business lies in balancing these elements. Users may not have an explicit problem that ads solve, but businesses can design ad experiences that feel relevant, unobtrusive, and beneficial to preserve engagement while driving revenue.

Here’s how a platform like YouTube might address this balance:

Scenario A: Business-Only Focus

Imagine YouTube increases the frequency of ads before and during videos to maximize revenue. While this may temporarily boost ad impressions (Z), it comes at a cost. Users grow frustrated with the interruptions and reduce their overall time on the platform (Y). Over time, this disengagement results in fewer opportunities to show ads, ultimately harming user entertainment (X) and revenue (Z).

Scenario B: User-Centric Approach

Alternatively, YouTube could leverage user behavior data to optimize the ad experience. For instance:

Show more personalized ads that align with user interests.

Offer non-intrusive formats like skippable ads or smaller banner ads.

Introduce value exchanges, such as allowing users to watch one long ad in exchange for uninterrupted viewing.

By respecting user intent (X) and enhancing the ad experience, YouTube retains engagement (Y), ensuring a steady stream of ad impressions and revenue (Z).

The Engagement-Revenue Sweet Spot

The trick is to find the sweet spot where engagement and revenue can cross to optimize both. This principle is true for any business where engagement is the driver of revenue.

Even in engagement-driven business models, user needs should anchor decisions. While ads may not directly solve users' intent of using an app, they can be delivered in ways that minimize disruption and, in some cases, enhance the user experience.

Broader Implications

Whether your business relies on subscriptions, transactions, or ads, the X → Y → Z framework remains a powerful way to align user and business needs. Focusing on user problems and tying them to business problems helps to improve business outcomes and removes the guesswork of experimentation.Neglecting the user in favor of short-term metrics might provide temporary gains, but it often leads to long-term losses in users and revenue.